If you missed part I, which discusses how water affects every aspect of the agricultural system from farm to fork, you can read it here: Part 1: Water Scarcity.

Part II of this series focuses on the often-overlooked aspect of how food gets to our tables. Items on grocery store shelves are part of a much larger piece of the supply chain puzzle than we realize or can see. The food system relies almost solely on those who toil in fields year-round, no matter the weather, to cultivate and harvest. These people are integral to the system, but the least represented. This post explores why Green Alpha understands that equity and equality across the entire food system are crucial variables in creating and investing for sustainable change.

There’s Just Not Enough for Everyone…Or is There?

Despite the repetitive narrative, hunger and food access are not yield issues. There is no global food shortage, nor are we on a trajectory that ends in one. The world’s food production rates have been steadily growing, now supplying 22% more calories per person than are needed. Unfortunately, these production increases are tied to increasingly harmful agricultural practices: monocropping, over tilling, excessive use of pesticides and herbicides, and other actions that degrade the land. Continuing these practices will lead to farmland so depleted that food production will cease.

In addition to misaligned yield versus needs, there is the issue of food waste. According to the USDA, the U.S. wastes “30-40 percent of the food supply” annually, equal to 242 pounds of food waste per person. Clearly more food production is not what’s needed; rather we must be more strategic about wasting less. By wasting this much food, land, water, labor, and energy are literally thrown away. The need to feed a growing population is often used as a justification for increasing yields at the expense of other things. But this reasoning overlooks the amount of food that ends up in landfills.

Waste Not, Want Not

Causes of food loss and waste occur at every stage of the production and supply chain. Most happens at retailers and in households.

In the retail world, restaurants serve portions that are too large to finish and are trashed; grocery stores overstock shelves, throwing away products as they reach their expiration date; and if produce doesn’t look perfect, farmers can’t sell it, leading to more waste.

At home, consumers forget about food in the back of refrigerators, and it goes bad; vegetables look wilted, so get tossed; date labels on food are confusing and misleading, causing perfectly good food to be thrown away.

Current farming practices deplete and degrade the soil and hurt the environment, which puts human health and future food production at great risk. According to the Rodale Institute, “over 40% of the current global harvest is wasted each year.” This is not an insignificant number, and it should be obvious that recent yield improvements are due to the farming practices we decry above. Society must alter these practices to continue producing enough food to feed the world in ways which do not deplete natural resources and harm production ability.

Hunger and food access are economic and social issues that, for the most part, result from bad policies and agricultural practices that create hunger. As a society, enough calories are produced to feed everyone. The issues lie in how food is produced, and ultimately wasted.

The Cost of Food

Production costs and food transport have led to drastically fluctuating global food costs over the last many years. This is frustrating and annoying for many people, but for those already vulnerable, it has far greater impact. Fluctuating costs mean the difference between ability to feed an entire family daily—or not. Those that are already least able to endure changing prices will find themselves pushed further into poverty and hunger.

Most people cannot fathom how much increasing food prices affect marginalized communities. While some countries have the capability to cushion the effects of rising food costs, others do not. Regardless, increased food prices disproportionately affect those who can least afford an increase.

Rising food costs and waste are not issues isolated to developing and emerging countries. Just this year, overall U.S. food prices have risen 11.4%, the largest yearly increase since 1979. And according to Pew Research, 24% of Americans report struggling to put food on the table each year. “The percentage of Americans who say they could not afford the food needed by their families at some point in the last years is three times that in Germany,” and more than twice the numbers in Italy and Canada.

The constantly changing cost of food around the globe are reflected in the ever-increasing numbers of farmers leaving the field for more competitive jobs. While falling food costs are usually seen in a positive light by consumers, producers and farm workers do not reap the same benefits. Reduced food prices trickle down the supply chain allowing consumers to enjoy lower spending, but reducing farmers’ profits from the work done to grow the food. Consumers frown at rising food costs; however, if food prices increase so farmers and producers can afford to feed their families, society benefits.

Another factor to consider is the link between volatile food prices and political instability. As illustrated in the chart below, there is a correlation between years in recent history marred by both political unrest and an increase in food prices. Which came—or comes—first is unknown. But what one can surmise is that both factors tend to happen at the same time, as evidenced in the current Ukraine conflict. “The price of basic food products has surged since the invasion of Ukraine” with food prices reaching an all-time high in March 2022.

The Food System Paradox

In this discussion of equality and access to food and water for all, it would be negligent to leave out the farmworkers growing our food. Issues related to the climate and food production are relevant to those who purchase and consume food, but also—and arguably more importantly—to farmworkers.

Our food systems are built around a paradox: the very people who grow the food that feeds us all struggle to put enough food on their own tables. The fruits and vegetables eaten on any given day may have been picked by farmworkers forced to work in oppressive heat, receiving poor pay, and who are otherwise exploited. Equity and equality—or the lack thereof—affect agricultural workers in major ways.

Barriers to Farmworker Equality

As noted in a recent article in Civil Eats, the consequences of extreme heat are deadly for farmworkers. There are over 200,000 farmworkers in the state of California alone, most of whom are migrants and only speak Spanish. Reports show that farm laborers “die of heat related causes at a rate of 20 times more than other professions.” Working in such extreme heat is inhumane, but unfortunately, few states have laws restricting farmworker exposure to extreme weather. Between 1992 and 2017, over 70,000 U.S. farmworkers suffered serious injury from heat stress and 815 died.

As climate change drives more extreme heat in agriculture-heavy regions, farmworkers will experience many more periods of dangerous, extended heat waves. Laborers that rely on farm work as their sole source of income may not be able to do so in the very near future.

Another issue affecting farmworker equality is little known, but surprisingly widespread: agricultural servitude. The very idea may seem impossible in a country as rich as the U.S., but communities like Immokalee, a former epicenter for modern day agricultural slavery, endure today. The Coalition of Immokalee Workers (CIW), located in the heart of agricultural land in Southwest Florida, arose in response to these conditions and focuses on exposing the inequality and outright slavery that still exists in the American food system. The CIW’s anti-slavery program has already uncovered and liberated over 1,200 workers held and forced to work against their will. Slavery in agriculture is a reality for numerous farmworkers; many laborers do not know their rights—or if they even have any.

In Florida alone, there have been over nine farm labor operations prosecuted for servitude in the last two decades. In 2008, dozens of tomato pickers in Florida and South Carolina employed by the Navarrete brothers escaped to tell their story. The employers pled guilty to “beating, threatening, restraining, and locking workers in trucks to force them to work as agricultural laborers… paying the workers minimal wages and driving the workers into debt…threatening physical harm if the workers left their employment before their debts had been repaid to the Navarrete family.”

The language barriers existing in the farming and agricultural industries are another cause of major frustration and occasional injury. For many field workers, it is challenging to gain access to information in their native language about standards that protect them from work-related casualties. Even though Spanish is the dominant language for over 62% of the U.S. farmworker population, pesticide labels are usually only in English. Many powerful pesticides used in agriculture are devoid of more than a single sentence in Spanish stating, “if you do not understand the label, find someone to explain it to you in detail.”

There are countless examples of farm workers experiencing sudden illness, blurred vision, irritated skin, and more after spraying pesticides. However, since workers cannot read the labels of the products sprayed, there is no way to find out if symptoms experienced correlate with those listed. Combine these instances with the fact that 90% of pesticide use in the United States is agricultural, and it is clear there is a disconnect between those manufacturing and those utilizing such harmful products.

It’s Not a Fair Trade

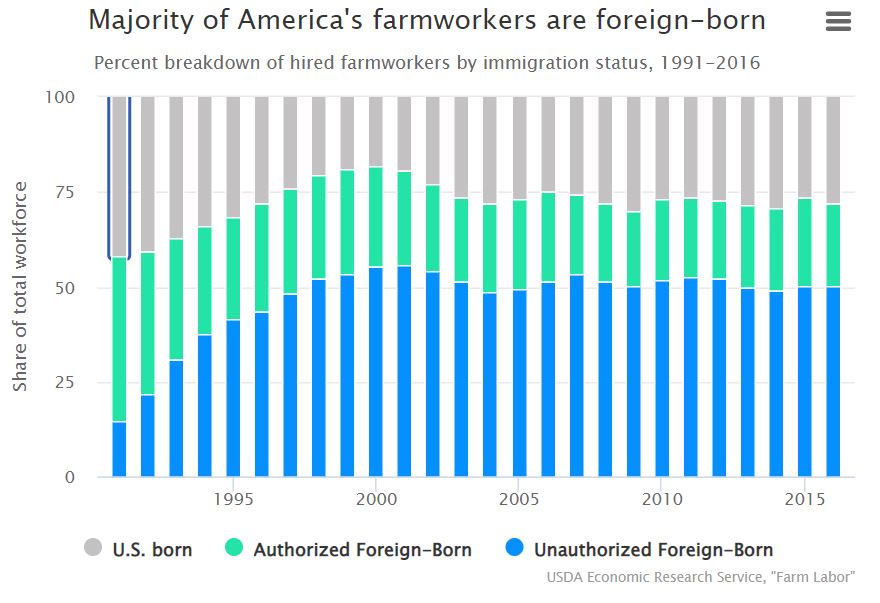

The American Farm Bureau Federation estimates that there are currently 2 million farmworkers in the United States, of which 73% were born outside of the country. According to the 2019-20 Department of Labor’s National Agricultural Workers Survey, 50% of farmworkers are undocumented. This number is likely much higher due to fear of self-reporting undocumented statuses. Immigrant farmworkers documented or not, pay taxes and contribute to the economy. Even so, they are not protected under the breadth of U.S. labor laws most Americans are, living in constant fear while working in less-than-ideal conditions. Undocumented immigrants pay an estimated 8% of their income in state and local taxes every year, on average earnings of $12,500 to $14,999 individually, and $17,500 to $19,999 for families.

For the most part, these workers and their families have lived in the United States for over 10 years and worked for one farm employer for seven of those years. Further, only 8% of farmworkers receive employer-provided health insurance. It is obvious there are major inequalities in the food system we are not privy to when choosing food at the grocery store.

Solution-Oriented Investing Doesn’t Include Silos

Considering the magnitude of the equity and equality issue in agriculture, what does this mean for Green Alpha and the Next Economy? According to Green Alpha’s thesis, the long term, sustainable economy will stand on the four pillars of the Next EconomyTM; social cohesion and equity are foundational. It is crucial to understand the issues farmworkers face every single day in order to make more informed investment decisions. For the firm, it means investing in companies seeking solutions to systemic issues as discussed here, and not in companies magnifying risks. We believe that to achieve the societal parity needed for true sustainability, one cannot invest in silos which leave any segment of the economy out.

###

Green Alpha is a registered trademark of Green Alpha Advisors, LLC. Green Alpha Investments is a registered trade name of Green Alpha Advisors, LLC. Green Alpha also owns the trademarks to “Next Economy,” “Investing in the Next Economy,” and “Investing for the Next Economy.” Green Alpha Advisors, LLC is an investment advisor registered with the U.S. SEC Registration as an investment advisor does not imply any certain level of skill or training. Nothing in this post should be construed to be individual investment, tax, or other personalized financial advice. Please see additional important disclosures here: https://greenalphaadvisors.com/about-us/legal-disclaimers/