Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property SocialSharing_Projects_Builder_Network::$profile_name is deprecated in /www/greenalphaadvisors_356/public/wp-content/plugins/social-share-buttons-by-supsystic/src/SocialSharing/Projects/Builder/Network.php on line 86

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property SocialSharing_Projects_Builder_Network::$sharesLists is deprecated in /www/greenalphaadvisors_356/public/wp-content/plugins/social-share-buttons-by-supsystic/src/SocialSharing/Projects/Builder/Network.php on line 121

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property SocialSharing_Projects_Builder_Network::$useShortUrl is deprecated in /www/greenalphaadvisors_356/public/wp-content/plugins/social-share-buttons-by-supsystic/src/SocialSharing/Projects/Builder/Network.php on line 146

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property SocialSharing_Projects_Builder_Network::$mail_to_default is deprecated in /www/greenalphaadvisors_356/public/wp-content/plugins/social-share-buttons-by-supsystic/src/SocialSharing/Projects/Builder/Network.php on line 151

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property SocialSharing_Projects_Builder_Network::$profile_name is deprecated in /www/greenalphaadvisors_356/public/wp-content/plugins/social-share-buttons-by-supsystic/src/SocialSharing/Projects/Builder/Network.php on line 86

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property SocialSharing_Projects_Builder_Network::$sharesLists is deprecated in /www/greenalphaadvisors_356/public/wp-content/plugins/social-share-buttons-by-supsystic/src/SocialSharing/Projects/Builder/Network.php on line 121

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property SocialSharing_Projects_Builder_Network::$useShortUrl is deprecated in /www/greenalphaadvisors_356/public/wp-content/plugins/social-share-buttons-by-supsystic/src/SocialSharing/Projects/Builder/Network.php on line 146

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property SocialSharing_Projects_Builder_Network::$mail_to_default is deprecated in /www/greenalphaadvisors_356/public/wp-content/plugins/social-share-buttons-by-supsystic/src/SocialSharing/Projects/Builder/Network.php on line 151

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property SocialSharing_Projects_Builder_Network::$profile_name is deprecated in /www/greenalphaadvisors_356/public/wp-content/plugins/social-share-buttons-by-supsystic/src/SocialSharing/Projects/Builder/Network.php on line 86

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property SocialSharing_Projects_Builder_Network::$sharesLists is deprecated in /www/greenalphaadvisors_356/public/wp-content/plugins/social-share-buttons-by-supsystic/src/SocialSharing/Projects/Builder/Network.php on line 121

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property SocialSharing_Projects_Builder_Network::$useShortUrl is deprecated in /www/greenalphaadvisors_356/public/wp-content/plugins/social-share-buttons-by-supsystic/src/SocialSharing/Projects/Builder/Network.php on line 146

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property SocialSharing_Projects_Builder_Network::$mail_to_default is deprecated in /www/greenalphaadvisors_356/public/wp-content/plugins/social-share-buttons-by-supsystic/src/SocialSharing/Projects/Builder/Network.php on line 151

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property SocialSharing_Projects_Builder_Network::$profile_name is deprecated in /www/greenalphaadvisors_356/public/wp-content/plugins/social-share-buttons-by-supsystic/src/SocialSharing/Projects/Builder/Network.php on line 86

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property SocialSharing_Projects_Builder_Network::$sharesLists is deprecated in /www/greenalphaadvisors_356/public/wp-content/plugins/social-share-buttons-by-supsystic/src/SocialSharing/Projects/Builder/Network.php on line 121

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property SocialSharing_Projects_Builder_Network::$useShortUrl is deprecated in /www/greenalphaadvisors_356/public/wp-content/plugins/social-share-buttons-by-supsystic/src/SocialSharing/Projects/Builder/Network.php on line 146

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property SocialSharing_Projects_Builder_Network::$mail_to_default is deprecated in /www/greenalphaadvisors_356/public/wp-content/plugins/social-share-buttons-by-supsystic/src/SocialSharing/Projects/Builder/Network.php on line 151

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property SocialSharing_Projects_Builder_Network::$profile_name is deprecated in /www/greenalphaadvisors_356/public/wp-content/plugins/social-share-buttons-by-supsystic/src/SocialSharing/Projects/Builder/Network.php on line 86

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property SocialSharing_Projects_Builder_Network::$sharesLists is deprecated in /www/greenalphaadvisors_356/public/wp-content/plugins/social-share-buttons-by-supsystic/src/SocialSharing/Projects/Builder/Network.php on line 121

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property SocialSharing_Projects_Builder_Network::$useShortUrl is deprecated in /www/greenalphaadvisors_356/public/wp-content/plugins/social-share-buttons-by-supsystic/src/SocialSharing/Projects/Builder/Network.php on line 146

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property SocialSharing_Projects_Builder_Network::$mail_to_default is deprecated in /www/greenalphaadvisors_356/public/wp-content/plugins/social-share-buttons-by-supsystic/src/SocialSharing/Projects/Builder/Network.php on line 151

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property SocialSharing_Projects_Builder_Network::$profile_name is deprecated in /www/greenalphaadvisors_356/public/wp-content/plugins/social-share-buttons-by-supsystic/src/SocialSharing/Projects/Builder/Network.php on line 86

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property SocialSharing_Projects_Builder_Network::$sharesLists is deprecated in /www/greenalphaadvisors_356/public/wp-content/plugins/social-share-buttons-by-supsystic/src/SocialSharing/Projects/Builder/Network.php on line 121

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property SocialSharing_Projects_Builder_Network::$useShortUrl is deprecated in /www/greenalphaadvisors_356/public/wp-content/plugins/social-share-buttons-by-supsystic/src/SocialSharing/Projects/Builder/Network.php on line 146

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property SocialSharing_Projects_Builder_Network::$mail_to_default is deprecated in /www/greenalphaadvisors_356/public/wp-content/plugins/social-share-buttons-by-supsystic/src/SocialSharing/Projects/Builder/Network.php on line 151

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property SocialSharing_Projects_Builder_Network::$profile_name is deprecated in /www/greenalphaadvisors_356/public/wp-content/plugins/social-share-buttons-by-supsystic/src/SocialSharing/Projects/Builder/Network.php on line 86

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property SocialSharing_Projects_Builder_Network::$sharesLists is deprecated in /www/greenalphaadvisors_356/public/wp-content/plugins/social-share-buttons-by-supsystic/src/SocialSharing/Projects/Builder/Network.php on line 121

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property SocialSharing_Projects_Builder_Network::$useShortUrl is deprecated in /www/greenalphaadvisors_356/public/wp-content/plugins/social-share-buttons-by-supsystic/src/SocialSharing/Projects/Builder/Network.php on line 146

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property SocialSharing_Projects_Builder_Network::$mail_to_default is deprecated in /www/greenalphaadvisors_356/public/wp-content/plugins/social-share-buttons-by-supsystic/src/SocialSharing/Projects/Builder/Network.php on line 151

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property SocialSharing_Projects_Builder_Network::$profile_name is deprecated in /www/greenalphaadvisors_356/public/wp-content/plugins/social-share-buttons-by-supsystic/src/SocialSharing/Projects/Builder/Network.php on line 86

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property SocialSharing_Projects_Builder_Network::$sharesLists is deprecated in /www/greenalphaadvisors_356/public/wp-content/plugins/social-share-buttons-by-supsystic/src/SocialSharing/Projects/Builder/Network.php on line 121

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property SocialSharing_Projects_Builder_Network::$useShortUrl is deprecated in /www/greenalphaadvisors_356/public/wp-content/plugins/social-share-buttons-by-supsystic/src/SocialSharing/Projects/Builder/Network.php on line 146

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property SocialSharing_Projects_Builder_Network::$mail_to_default is deprecated in /www/greenalphaadvisors_356/public/wp-content/plugins/social-share-buttons-by-supsystic/src/SocialSharing/Projects/Builder/Network.php on line 151

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property SocialSharing_Projects_Builder_Network::$profile_name is deprecated in /www/greenalphaadvisors_356/public/wp-content/plugins/social-share-buttons-by-supsystic/src/SocialSharing/Projects/Builder/Network.php on line 86

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property SocialSharing_Projects_Builder_Network::$sharesLists is deprecated in /www/greenalphaadvisors_356/public/wp-content/plugins/social-share-buttons-by-supsystic/src/SocialSharing/Projects/Builder/Network.php on line 121

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property SocialSharing_Projects_Builder_Network::$useShortUrl is deprecated in /www/greenalphaadvisors_356/public/wp-content/plugins/social-share-buttons-by-supsystic/src/SocialSharing/Projects/Builder/Network.php on line 146

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property SocialSharing_Projects_Builder_Network::$mail_to_default is deprecated in /www/greenalphaadvisors_356/public/wp-content/plugins/social-share-buttons-by-supsystic/src/SocialSharing/Projects/Builder/Network.php on line 151

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property SocialSharing_Projects_Builder_Network::$profile_name is deprecated in /www/greenalphaadvisors_356/public/wp-content/plugins/social-share-buttons-by-supsystic/src/SocialSharing/Projects/Builder/Network.php on line 86

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property SocialSharing_Projects_Builder_Network::$sharesLists is deprecated in /www/greenalphaadvisors_356/public/wp-content/plugins/social-share-buttons-by-supsystic/src/SocialSharing/Projects/Builder/Network.php on line 121

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property SocialSharing_Projects_Builder_Network::$useShortUrl is deprecated in /www/greenalphaadvisors_356/public/wp-content/plugins/social-share-buttons-by-supsystic/src/SocialSharing/Projects/Builder/Network.php on line 146

Deprecated: Creation of dynamic property SocialSharing_Projects_Builder_Network::$mail_to_default is deprecated in /www/greenalphaadvisors_356/public/wp-content/plugins/social-share-buttons-by-supsystic/src/SocialSharing/Projects/Builder/Network.php on line 151

Untangling Science from Spin

By Garvin Jabusch

An edited version of this article was published by Worth

The use of the term “Anthropocene” outside the purview of geology, which defines it in terms of technical stratigraphy, is an awareness campaign, a political project. Lots of its boosters are hoping that, if they can reveal the destructive practices of modern civilization as so significant that they’ve triggered a geological designation requirement, people may begin to take the crises of climate and resource degradation seriously.

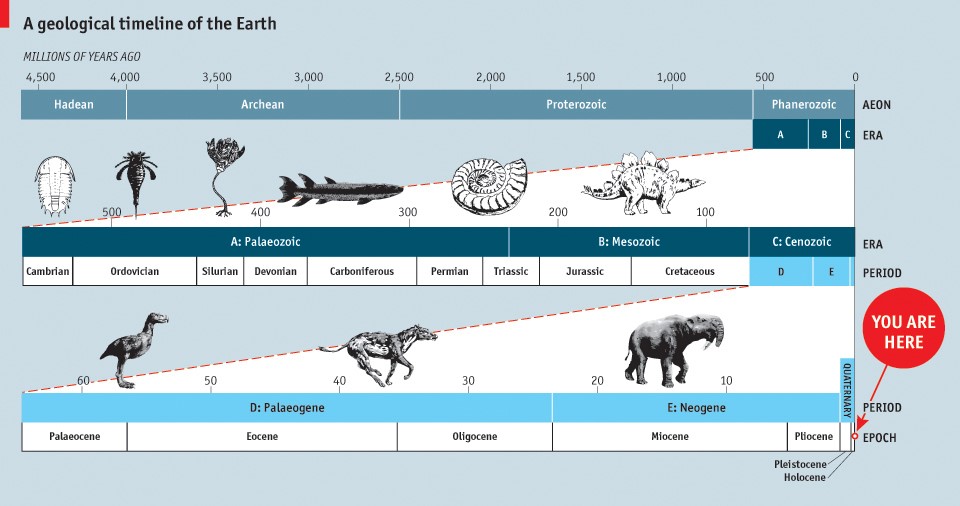

Chronologically, the Anthropocene, if formally implemented, is intended to follow upon and replace the Holocene, in which we are now living, and which previously replaced the Pleistocene epoch, which ended about 12,000 years ago. Interestingly, the Holocene seems to have itself been conjured, more than anything else, to indicate humanity’s arrival as the dominant force on the planet.

The geological record shows that the boundary between the Pleistocene and the Holocene is a distinction without a difference, and, scientifically speaking, we could just as easily have labeled the last 12,000 years or so the late Pleistocene (or perhaps the latest of the many Pleistocene interglacial events). Can that be right, though? Isn’t the Holocene an inviolable definition of science? Let’s look at that, starting with the definitional requirements for establishing an epoch.

An Epoch, in geology, is a chronostratigraphic unit’s geochronologic equivalent, which is “derived from a geographic feature in the vicinity of its stratotype.” Or, as Wikipedia more plainly puts it, “epochs are normally separated by significant changes in the rock layers to which they correspond.” For an Epoch to be defined, whatever is going on with the world’s geology needs to be significant enough that it is leaving behind a clearly identifiable, distinct stratigraphic layer. What satisfies this requirement for the Holocene is ambiguous, but generally, “most geologists and paleontologists designate the beginning of a new epoch—the Holocene—at approximately 11,700 years ago, a time coincident with the sudden ending of the Younger Dryas cool phase” (from Britannica). That is, as of the ending of the most recent Pleistocene glacial event, or ice age, which is not particularly distinct from the cycle of glacial-interglacial-glacial events that had been going on for most of the Pleistocene’s 1.8 million year run. But, does the ending of the cool phase definition work with the stratigraphic layer requirement? Again from Britannica, “An absolute chronology provided by radiocarbon dating permits temporal correlation, even if the deposits are discontinuous or physically different. Analysis of Holocene deposits requires chronostratigraphic correlations of discontinuous and dissimilar deposits to allow an interpretation of local, regional, continental, and global conditions” [italics mine]. So the stratigraphy picture is tortured, at best. That means the scientific criteria for the establishment of the Holocene isn’t strong.

What is clear is that the defined start of the Holocene is coincident with the emergence of larger human settlements and sedentary agriculture; the beginning of civilization as we might recognize it today. So one could argue that the Holocene designation exists because we collectively agreed that civilization is important enough that it belongs in its own Epoch, whether the geological definition supports that or not. By more objective criteria, the present moment is still the Pleistocene, but the Holocene has been formalized and institutionalized, and so we all just go with it.

So now after just 12,000 years in the current Holocene (epochs can stretch into the tens of millions of years), science is attempting to determine whether we should up and establish yet another new one, the Anthropocene. So, what criteria exist to justify this new, new designation? As it turns out, kind of a lot.

The list of solid, enduring Anthropocene markers includes “rapid global dissemination of novel materials including elemental aluminum, concrete, and plastics that form abundant, rapidly evolving ‘technofossils.’ Fossil fuel combustion has disseminated black carbon, inorganic ash spheres, and spherical carbonaceous particles worldwide, with a near-synchronous global increase around 1950. Anthropogenic sedimentary fluxes have intensified, including enhanced erosion caused by deforestation and road construction.” This was the summary from a large, multi-institutional, interdisciplinary study titled, “The Anthropocene is functionally and stratigraphically distinct from the Holocene.”

And that’s not all. “Atmospheric CO2 and CH4 concentrations depart from Holocene and even Quaternary patterns starting at ~1850, and more markedly at ~1950, with an associated steep fall in δ13C that is captured by tree rings and calcareous fossils. An average global temperature increase of 0.6o to 0.9oC from 1900 to the present, occurring predominantly in the past 50 years, is now rising beyond the Holocene variation of the past 1400 years, accompanied by a modest enrichment of δ18O in Greenland ice starting at ~1900. Global sea levels increased at 3.2 ± 0.4 mm/year from 1993 to 2010 and are now rising above Late Holocene rates.” Yeah, the Anthropocene is gonna leave a mark.

Where the Holocene is a designation given by humanity to itself to validate and solidify our uniqueness, yet lacking in globally continuous geologic markers, the Anthropocene really is leaving a large, clear stratigraphic signature. Unlike with the Holocene, far future geologists will be able to look at the strata associated with the Anthropocene and say, “yep, there it is. Plain as day.”

Scientifically, the Anthropocene is more of a clear, distinct phenomenon than the Holocene ever was, and, sociologically, it serves a more important purpose. Yes, the Anthropocene is on one level a political construct. Yes, it is also real. That is has become objectively real mostly since 1950, where epochs usually take millennia if not millions of years to establish their footprint, should tell us how serious the climate crisis really is.

Why does any of this matter to an asset manager? Because it’s all part of understanding the stack of economy-and-civilization-level risks that faces investors over the next decade, and really, over any time period. Think investment risk is defined by price volatility? It’s not. It’s defined by the cluster of threats that have arrived in tandem with the all-too-real Anthropocene.

###

Important Disclosures https://greenalphaadvisors.com/about-us/legal-disclaimers/